In an ideal world, you’ve been exercising your crisis team for years; team members know each other well, they follow a process fluently and understand the full range of risk scenarios. You have practised activation, use of information sharing and communications systems; you have slick meeting arrangements, including virtual and alternate locations.

In the real world, you may be missing some of these elements and that is not surprising given the relentless competition for management time. For 99.9% of the year, crisis management capability doesn’t seem like a good investment. However, in that 0.1% you will, whether you like it or not, be spending more time and money than you ever wanted to.

Common problems to avoid

Having been involved in many live crises, ranging from major industrial accident, through to terror attack, pressure group activism, kidnap, extortion and cyber-attack, we’ve found some common problems you’ll definitely want to avoid:

- Over-confidence. This usually comes from either a faulty appreciation of the situation or a faulty appreciation of a leader’s capability. An old-school, autocratic approach usually prevents a multi-disciplinary team from bringing its combined knowledge and skills to bear on the real issues at hand.

- Under-confidence. We have seen otherwise competent business leaders avoid managing a crisis because, although they know deep down there is potential impact to the business as a whole, they defer to functional leads like communications or legal to make the problem go away.

- Operational dominance. This is particularly common where understanding of the operational ‘fix’ is held by a team of technical experts. For example, the IT incident management team will be dealing with containing an attack on IT systems – the ‘fix’, but they should not be expected to address the strategic business impacts: that is for the crisis team.

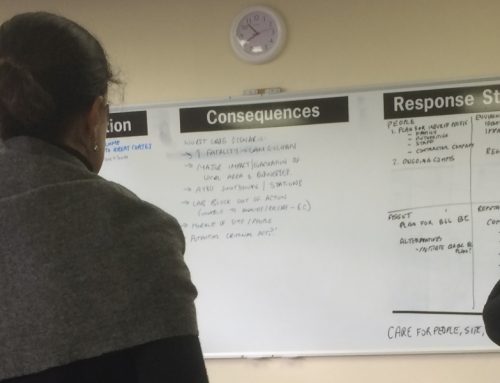

Structure and process

So, rather than hoping for the best and risking any of those default situations, we strongly encourage organisations to follow a couple of key principles: The fist is to establish a simple process they can follow once they get in the room (or the virtual room). There is a good reason great crisis teams do this: they want to maintain flexibility to respond, but they also want to hit the ground running. When Gold Command gets notification of another terror attack, he or she doesn’t start thinking about a framework for decision-making: it is already embedded in their brain (and probably backed up on a card in their top pocket). COBR does not sit around debating the best way to think about the problem: it already has a coordinator running a familiar process for information management and decision-making, with all the right people in the right places, doing the right things. For corporates, the process can be strikingly simple, but very effective in ensuring the crisis team takes vital first steps. It also ensures that outputs are executable; and that the end-to-end process is auditable (and you have a defensible position years later in court).

Leader and Facilitator roles

The second is to separate out the roles of Leader and Facilitator (some people prefer the term Coordinator, but this suggests a role less important than it really is). The Leader gives direction and authority to the team’s activities, while the Facilitator handles the procedure. It seems obvious: this model has been widely used in business and elsewhere down the ages, but surprisingly few crisis teams invest much in the Facilitator role. Having a really effective Facilitator running the room means everyone else can do their job better: the leader can stand back and take an overview, while functional roles like Legal, Finance and Communications can concentrate on what they are paid for. Naturally, each business will decide how it resources this vital Facilitator role. We’ve seen some businesses invest in crisis training as a form of leadership development for high-potential managers. Others outsource it, retaining our services or similar. Either way, it represents a deliberate risk management decision and pays dividends.

What makes the difference?

Eddistone Consulting have drawn together a team of specialists who have extensive collective experience, coming from industry, the emergency response services, the multi-agency response community, health & safety and education backgrounds, to develop and deliver a competency-based training and exercise framework with identified performance deliverables to measure effectiveness and assure competence.

We use a proven systematic approach that explores how to respond. We have core methodologies for each response level of Emergency, Incident and Crisis (Operational, Tactical and Strategic) management. The credibility and reality of our exercises, experienced in a safe environment where real learning takes place, is always valued by our customers.

How we can help

We recognise that many of our clients, especially in the COMAH-regulated sector, are under pressure to maintain mandated emergency management capacity. We are committed to providing you with emergency management support wherever possible throughout this pandemic. This is important to ensure that you do not fall behind with your scheduling backlog and to maintain the required capacity, despite the impact of absence and illness on safety-critical roles. We have two strategies to help you achieve this:

- We have developed remote methods for training and assessment, coupled with remote mentoring for the development of key roles. This facilitates accelerated learning and makes the best use of technology and advanced learning practices.

- We have a pool of experts ready to provide direct support, both remotely and in person, to reinforce capacity and mentor your existing capability. Our team of experts is ready to stand alongside your key emergency response personnel.

Contact us to discuss how we can help you.